Hail

Hail is one of the most destructive types of severe weather. While often overshadowed by tornadoes, hail causes millions of dollars in damage each year. Hail stones come in various sizes and shapes and can cause large amounts of damage to property. Hail is found in many thunderstorms and often accompanies storms that produce strong winds and tornadoes.

What is Hail?

Hail stones are a frozen form of precipitation that occurs when thunderstorm updrafts lift rain above the freezing level in the atmosphere. When hail stones become too heavy to be lifted by the updraft, they fall to the ground.

While most thunderstorms form hail, hail does not always make it all the way to the ground as hail. If the hail stone is small enough, the stone melts in the warmest portions of the atmosphere which are near the ground. For hail to become large enough to reach the surface, the stone must grow large enough in the thunderstorm before falling through the warm lower atmosphere. The same mechanisms that help create tornadic storms-low level moisture, lift, atmospheric instability and wind shear-usually need to be in place for hail stones to become large enough to fall all the way to the surface.

How Hail Forms

Hail forms when a thunderstorm updraft lifts a water droplet above the freezing level in the atmosphere. The frozen water droplet then accretes super-cooled water or water vapor, which freezes once it comes in contact with the frozen droplet. This process causes a hailstone to grow.

Hail is often confused with other types of freezing precipitation such as sleet. Sleet is found mainly during the cold season and does not occur in thunderstorms. Hail, in comparison, is only found in thunderstorms where updrafts in the thunderstorm forces raindrops further up in the atmosphere to freeze.

A hailstone that underwent wet growth, causing the hailstone to have a spiked and bumpy appearance. Image courtesy of NWS-Wichita, KS.

Hailstones often have a ringed appearance, as the hailstone moves into different concentrations of water vapor and super-cooled water through the updraft. Image courtesy of NOAA Photo Library.

In many cases, hailstones have a ringed appearance (left). The rings represent the different environments the hailstone experiences while moving through the updraft. When the hailstone is in an environment where mainly water vapor is present, a white or opaque layer forms. This occurs because small air pockets are trapped between the vapor particles as they freeze. When the hailstone is in an environment of mainly super-cooled water, a clear layer forms as the super-cooled water freezes instantaneously to the hailstone.

Hailstones can also grow by sticking to each other in a process called wet growth. Larger hailstones will ascend through the updraft at a slower speed than smaller hailstones. If the outer coating of these hailstones is not completely frozen, they can collide with each other and stick. If this process happens over and over again, a hailstone can grow very quickly. When these aggregated hailstones hit the ground, they often have a bumpy or spiky appearance (right), as the smaller hailstones that make up the larger hailstone maintain their individual shapes.

Hail Size

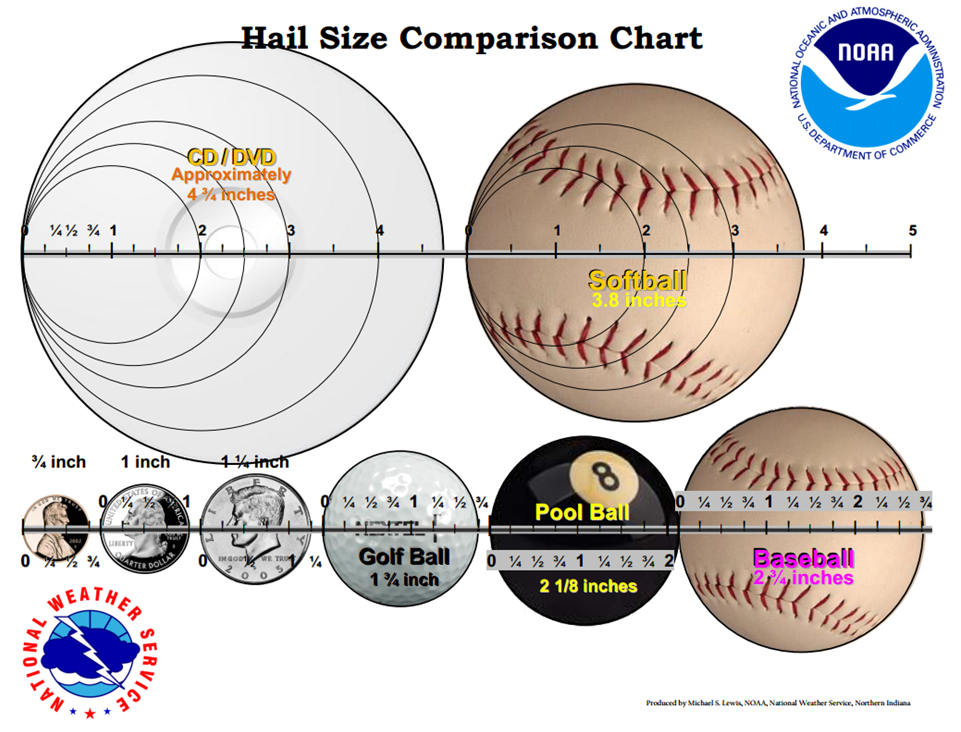

Hail sizes can differ greatly from one storm to another depending on the strength of the storm’s updraft. Stronger updrafts can create larger hailstones, which in turn causes more damage. This makes reporting the size of hail important for public safety. The preferred hail measurement method is to use a ruler to measure the diameter of the hail stone along its longest axis. However, various coins and balls are often used when reporting hail size. It is not advised to use marbles as a size indicator as marbles come in many different shapes and sizes.

This hail size chart outlines the types of objects that the National Weather Service prefers

to be used when reporting hail. Using marbles as size indicator isn’t advised.

While this may look like snow on the ground, it’s actually hail! A late May thunderstorm in Denver dropped nearly 5 inches of hail on the ground. Image courtesy of Denver Police Department.

Hail is considered severe if a thunderstorm produces hail stones larger than one inch in diameter, or larger than the size of a quarter. This size was determined by damage assessments and insurance claims across the U.S. Significant sized hail is considered any hail stone larger than 2 inches in diameter, or larger than the size of a pool ball. The largest hailstone ever recorded was in Vivian, South Dakota, with a whopping 8 inch diameter and weighing nearly two pounds!

The largest recorded hailstone in the United States, from Vivian, SD on July 23, 2010. It’s diameter was 8 inches, with an 18.625 inch circumference. Its official weight was 1.9375 pounds. The hailstone was larger, but a power outage caused some melting of the stone. Courtesy NWS-Aberdeen, SD.

Like tornadoes, hail tends to affect isolated areas. The types of thunderstorms that create these kinds of severe weather are normally isolated in nature. This means that one side of a road may have baseball size hail while the other side has nothing. This makes warning for and reporting hail somewhat problematic. Some hail storms can even move so slowly that the hail accumulates like snow. A storm in the Denver area caused around 5 inches of hail to accumulate on the ground!

Detection of Hail

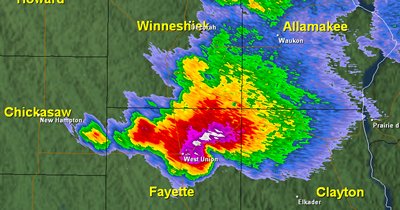

A storm with a significant hail core in northeastern Iowa, as seen by the areas with a reflectivity in the purple and white shadings. Image courtesy of NWS-La Crosse.

Much like tornadoes, hail detection has become much easier with Doppler radar for weather. Because hail stones are usually much larger in size than the biggest raindrops, they return a much higher reflectivity on a Doppler radar. When radar detects a higher reflectivity than possible with rainfall, hail is likely occurring. Problems can arise, however, with smaller hail that’s mixed with rain. The rain and hail mixture can show a reflectivity that’s below the criteria for hail. This makes hail detection on classic Doppler weather radar difficult in many cases.

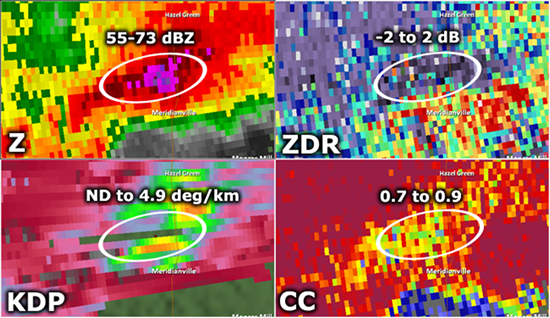

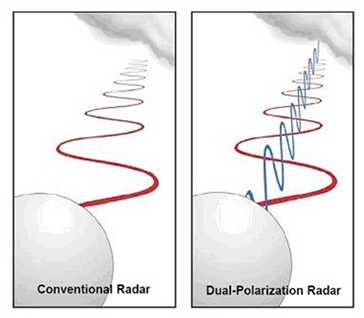

With recent upgrades to the weather radar technology in the U.S., hail detection has become much easier. Dual-Pol, or Dual Polarization radar data, allows hail to be singled out from rainfall due to their differing shapes. Rain drops tend to fall in the shape of a hamburger bun as air resistance flattens the drop, giving them a greater width than height. Hail stones tend to be irregular in shape, but look spherical as they tumble through the air, with their height and width similar in nature. Dual-Pol radar can detect both the horizontal and vertical element of a raindrop, hailstone or any meteorological target, which gives meteorologists a better picture of what is falling from the sky.

Meteorologists are able to look at specialized products from Dual-Pol radars to better detect and predict hail. These products give meteorologists information on the extent of hail, whether the hail is coated in liquid water, and possibly estimate the size of the hail. All of these products help meteorologists forecast where the hail storm is heading and know when a hail threat has passed.

A storm with hail north of Huntsville, AL on March 2, 2012 as seen with classic reflectivity (Z) and Dual-Pol products Differential Reflectivity (ZDR) Specific Differential Phase (KDP) and Correlation Coefficient (CC). These Dual-Pol products help meteorologists better predict and warn for hail. Image courtesy of NWS-Jackson, MS.

While conventional radar can only scan one axis of a meteorological target, Dual-Pol radars can scan both horizontal and vertical axes of the target. Image courtesy of NOAA Radar Operations Center.

^Top

Hail Climatology

Like tornadoes, hail occurs in many parts of the world. However, it occurs most often in the United States, where the topography and geography are good for producing strong thunderstorms. Hail tends to follow a similar pattern to tornadoes when it comes to where it is most frequently found.

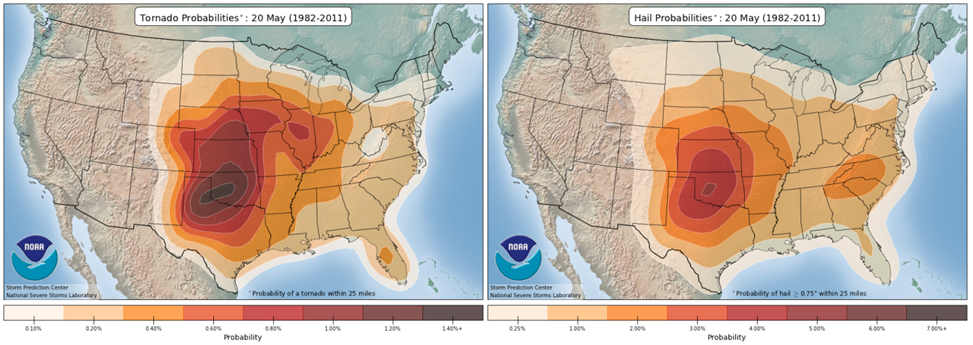

Tornado probabilities (left) follow a similar pattern to hail

probabilities (right) as storms that often cause hail also can cause tornadoes. Note: The color scales represent

different percentages of probability.

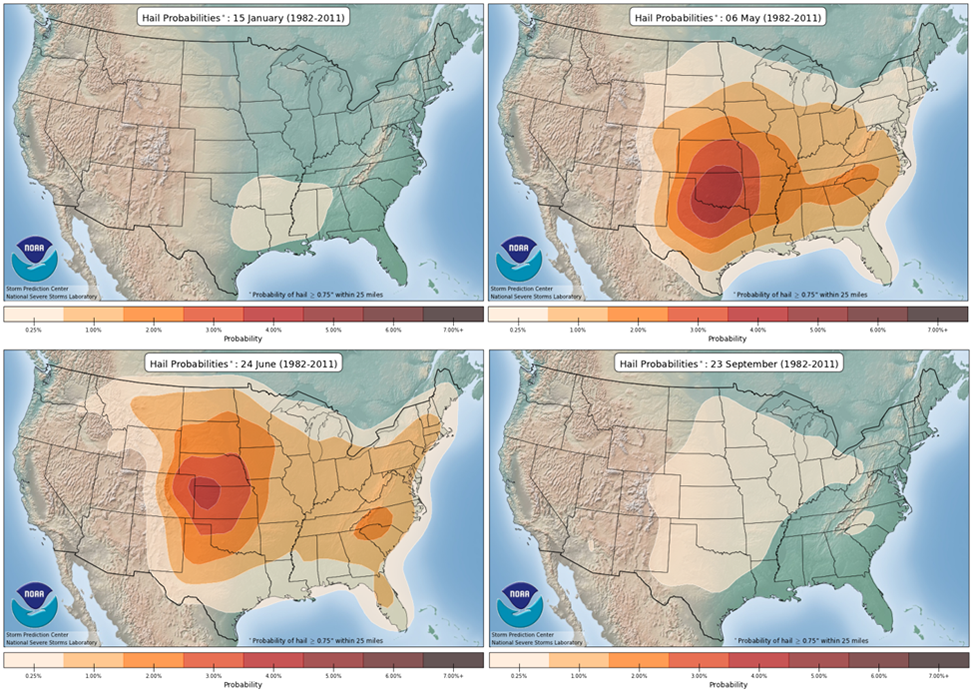

In January, hail is most frequently found along the Gulf of Mexico, mainly along the Mississippi and Red River Valleys. However, the updrafts with these storms aren’t usually strong enough to create hail much larger than 1 inch in diameter. As winter moves into spring, the probability increases for hail. The highest probabilities move into the South Central U.S where the dryline helps create a good environment for strong thunderstorms. As the dryline weakens in the South Central U.S. as spring becomes summer, the highest hail probabilities shift north into the High Plains. By the end of September, the probability of hail has greatly diminished across the country with probabilities continuing to diminish into winter.

The probability of seeing hail 0.75 inches in diameter or greater

for four different time periods throughout the year. The highest chances for hail on any given day in the U.S.

are in the late spring and early summer months in the Great Plains. Higher elevation in the Plains helps

hailstones grow larger as the freezing level

of the atmosphere is closer to the ground.

While hail can be found almost anywhere east of the Rockies in the United States, the largest and most frequent hail tends to be in the Great Plains. The Great Plains are higher in elevation than most of the eastern half of the country. The higher elevation places the freezing level in the atmosphere closer to the ground, which allows hail to occur in a less intense thunderstorm than in other parts of the country. In stronger thunderstorms, hailstones spend more time above the freezing level in the updraft. More time above the freezing level gives the hailstone a greater ability to be coated in more super-cooled water or water vapor, or collide with other hailstones to undergo wet growth. This in turn allows hailstones to become larger than in the lower elevation areas of the Midwest and Northeast United States.

^TopHail Damage

Hail can be incredibly destructive to crops and property. As a hailstone increases in size, its terminal velocity, or top possible speed also increases, which causes more damage to anything the hail stone strikes. Baseball size hail can reach speeds of around 70 miles per hour as it reaches the ground. Larger hailstones can reach upwards of 90 to 100 miles per hour. That’s like getting hit by a Major League fastball!

Hail damage to corn. Image courtesy of NWS-Hastings, NE.

Crop Damage

Crops can be particularly susceptible to hail damage. Smaller grains such as wheat and barley may see large yield losses when a significant hail event occurs. Corn plants in their early to middle stages of growth usually can recover from hail trauma, but more mature plants are more susceptible to damage. Hail can destroy the plant’s leaves and knock over stalks, which can ultimately sterilize or kill the plant. Farmers often take out crop insurance to protect from lost yields caused by hail damage.

Property Damage

Hail can pose a large threat to property as well. Cars are often the most susceptible to damage as dents are easily made in the sheet metal covering the car. Sunroofs, moon roofs and windshields can be easily cracked and shattered by hail, which can be dangerous if people are inside the vehicle. Hail also causes major damage to roofing shingles. Larger hailstones can even puncture right through roofs and into a house! Windblown hail can break windows and shred siding from houses. All of this damage leads to costly repairs and replacements. Using current dollars, more than $50 Billion of property damage has been done by hail in the United States since 1949. That comes to over $850 million in hail damage done annually.

Cars are a dangerous place to be during a hailstorm. Windows and windshields can shatter and injure people inside the car. Image courtesy of NWS-St. Louis, MO.

Wind-blown hail can rip siding right off a house, making for costly repairs. Over $850 million of hail damage is occurs every year. Image courtesy of NWS-Lubbock, TX.

^Top

What To Do When Caught in a Hailstorm

If you are in a building:

Move into an interior room away from windows. Wind-blown hail can shatter windows which can cause injury. Even if hail has stopped falling, stay inside as other thunderstorm dangers such as lightning and strong winds are still possible. Your safety is paramount!

If you are driving:

Pull out of the flow of traffic into a nearby parking lot or onto the side of the road. Make sure to engage your emergency flashers to warn other vehicles that you have stopped. By driving through hail, you are only making it easier for hail to damage your vehicle. Hail can easily damage windows and windshields in vehicles. Turn your body and head inwards towards the center of the vehicle to protect your head from breaking glass. Use blankets and other soft materials to cover yourself in case glass hits you. If your vehicle has a sunroof or moon roof, move out from under the glass as sunroofs and moon roofs are particularly susceptible to breaking from hail.

If you are outside:

Get inside a nearby building or car immediately! Because of the hazards that can occur if you are in a car during a hailstorm, it is highly preferred to find a nearby building. If there are no cars or buildings nearby, do everything possible to protect your head! The most deadly injuries from hail are ones where someone is hit in the head by hail. Use absolutely everything you can to shield your head from falling hail. Even taking off your shoes and placing them over your head will give some protection! Even small hail can do serious damage to your body!

While it may seem like a good idea to stand underneath a tree for protection, it only increases your risk of injury. Trees can easily be struck by lightning, and standing underneath one increases your chances of being electrocuted.

Hail is easily the most immediately destructive form of precipitation. Do your part to be weatherwise and have a NOAA All Hazards radio in your home or business. Also, stay up to date with local thunderstorm forecasts from the National Weather Service and thunderstorm outlooks from the Storm Prediction Center, you can stay safe from the dangerous threat of hail.

^Top

A hail pad used by CoCoRaHS observers. These pads can be used to determine the largest, most common and average hail size.

Hail Resources

Where to Find Hail Data

Several national networks save hail data from storms that are for public use. The National Severe Storms Lab in partnership with the Storm Prediction Center archives all of their storm reports from the public and public service employees. This Storm Events Database contains all reported data from 1950 to present. You can choose to see hail, tornadoes or any other type of severe weather report.

The Community Collaborative Rain, Hail & Snow Network (CoCoRaHS) also collects hail data from the members in their volunteer network. In many cases, observers use a device called a hail pad. Falling hail leaves dents in the foil wrapped pad. The hail pad can then be analyzed to determine the largest hailstones, the most common hailstone size, and the average hailstone size. These data are publicly available in the "View Data" section on the CoCoRaHS website.

Further Reading

- NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory Severe Weather 101 – Hail

- Hailstorms Across the Nation-An Atlas about Hail and Its Damages

- Hail Climatologies

Academic Papers on Hail Formation:

- Airflow and Hail Growth in a Severe Northern High Plains Supercell L. Jay Miller, John D. Tuttle, Charles A. Knight. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. Volume 45, Issue 4 (February 1988) pp. 736-762.

- Radar Echo

Structure, Air Motion and Hail Formation in a Large Stationary Multicellular Thunderstorm. L.

J. Miller, J. C. Fankhauser. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. Volume 40, Issue 10 (October 1983) pp.

2399-2418.

- Precipitation Production in a Large Montana Hailstorm: Airflow and Particle Growth

Trajectories. L. Jay Miller, John D. Tuttle, G. Brant Foote. Journal of the Atmospheric

Sciences. Volume 47, Issue 13 (July 1990) pp. 1619-1646.

- Hail Growth Mechanisms in a Colorado Storm: Part II: Hail Formation Processes. Andrew J. Heymsfield, Arthur R. Jameson, Harold W. Frank. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. Volume 37, Issue 8 (August 1980) pp. 1779-1807.

^Top